Hello and happy February! Look at this, a month went by. In any case, I decided to dedicate an evening this week to Animal at last – here are my thoughts on the two hundred minutes I devoted to this film.

This week’s movie: Animal.

Perhaps it’s useful to think of Animal as the anti-Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham. Director and writer Sandeep Reddy Vanga’s film follows similar beats – a disgraced son leaves the family home, only to return years later to seek his father’s approval. The son hero-worships the father, even when and after the father spurns him. But where K3G was ‘all about loving your parents’, Reddy Vanga’s Animal is all about avenging your father against every conceivable odd.

Or perhaps we could look at the film as Reddy Vanga’s ‘violent film’, a self-confessed fuck-you to the critics who assailed his previous work, the twin movies Arjun Reddy and Kabir Singh, as violent. Indeed, Animal is brutally, relentlessly violent: when the men aren’t slaughtering each other (as the women look on, pained), they’re screaming insult, planning elaborate murder, brandishing ugly guns in broad daylight, threatening each other. At one point, the protagonist, a singularly horrendous figure whose name is only revealed halfway through (which means, I guess, I can’t tell you what it is), describes exactly what kind of slap he’ll administer to his wife if she steps out of line.

Or you could look at Animal through a political lens. Its gender politics, for one: the protagonist (Ranbir Kapoor, thoroughly committed but draining to watch) marries a woman he claims he loved as a teen, after he shows up at her engagement ceremony and lets her know that he is an alpha male unlike her fiancé. She (Geetanjali, played by a ferocious Rashmika Mandanna) calls off her wedding and scurries over to him, saying very little. Thankfully, Geetanjali has more dialogue than Preeti from Kabir Singh, but in key scenes, where saying something might help people understand, such as when she and the protagonist confront her family and his father, Geetanjali stays quiet. Other women, including the protagonists’ sisters (Saloni Batra and Anshul Chauhan) and mother (poor Charu Shankar, who’s only a year older than Kapoor), are each given spark and fire, but always in deference to the men in their lives. This alone is not a problem: women across the world have lived lives like this for centuries – still do – and their stories deserve to be told. Except that Animal is not interested in their stories, merely in how they can contribute to their men’s stories.

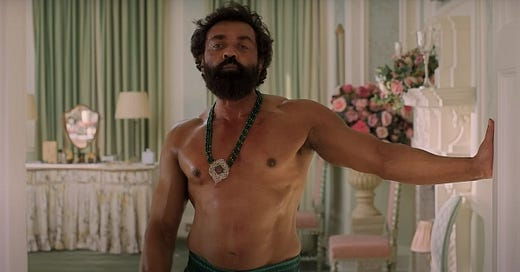

There’s also the film’s lens on its Muslim ‘villains’, who are painted as savage, bloodthirsty beasts (one of them is literally a butcher), with multiple wives and too many children to count. Bobby Deol shows up in the film’s third hour (its third hour, for god’s sake) as Abrar Haque, a debauched man marrying his third wife – his first two share cigarettes in the next room, claiming they only married him for his money. When Abrar is cornered at the end of the film, he abandons all three women, including the newest one who’s pregnant. Now, the protagonist, a Hindu, is also portrayed as a bloodthirsty animal (hence the film’s title), indeed a terrorist, denounced by both a pundit and a Catholic priest, but his family repeatedly stands by him publicly. He may have scarring altercations with his wife, may threaten violence and grab her throat, but at the slightest doubt raised about his husband skills, she leaps into a long defence, concluding that he has been all sorts of family to her.

All this to say that there’s multiple ways to approach Animal, a film that blares on for three hours and twenty minutes. But the salient question in my mind was – why would you want to? What is the point of this film? Reddy Vanga said recently (the link is a spoiler!) that he wanted to underline, by the film’s end, the futility of the protagonist’s quest. But what he forgets to do is provide an adequate impetus for the quest. The protagonist is introduced to us in two shades: as an arrogant, abrasive young man, and as a son whose desperation for his father’s love is a life force. The theme song of the film, a plaintive ballad called ‘Papa Meri Jaan’ (‘papa my love’), underlines the protagonist’s tireless striving for the love and approval of his father Balbir (Anil Kapoor). But why, even as an adult, does his adherence to this man not waver? Balbir spurns him, humiliates him, refuses to reconcile with him, throws him out of the house; by all accounts, Balbir has given his son a miserably deprived childhood. Yet when Balbir is attacked, the protagonist comes thundering home, laying waste to the men who masterminded the attack. There didn’t seem to be any real reason for this extreme behaviour, except that the protagonist is a psychopath. Perhaps that is Reddy Vanga’s reasoning.

The centrepiece of all these actions is a massive action scene in a hotel, where the villains wear animal masks, the protagonist’s supporters sing a rousing Punjabi folk ballad called ‘Arjan Vailly’, and a gigantic machine-gun-vehicle makes an earth-shattering appearance, massacring scores of men. The protagonist operates this vehicle, his body quivering as he does it. This quivering, were it not contextualised as occurring mid-battle, resembles a body masturbating. And, in a way, the protagonist is masturbating: he gets off, clearly, on bumping people off and putting his body in extreme situations. He’s also always talking about sex, his penis, its size, his sex drive, other people’s sexual habits… At one point, he’s playing his wife an audio recording of the first time they had sex, a night that also involved him putting water in his mouth and then draining it into hers as they kiss. The man, and, by extension, the film around him, is a towering embodiment of chest-thumping sexual assertion. It’s one long, two-hundred-minute ordeal of screaming machismo. And it’s exhausting.

Animal is on Netflix.